A service desk analyst on IT Services’ customer experience team, James O’Bryant is a teacher by nature—and likely by birthright.

“My father was a true believer in how education can change your life,” said O’Bryant, who earned a B.A. in education from Northeastern in 1987. “He promoted that message everywhere he went.”

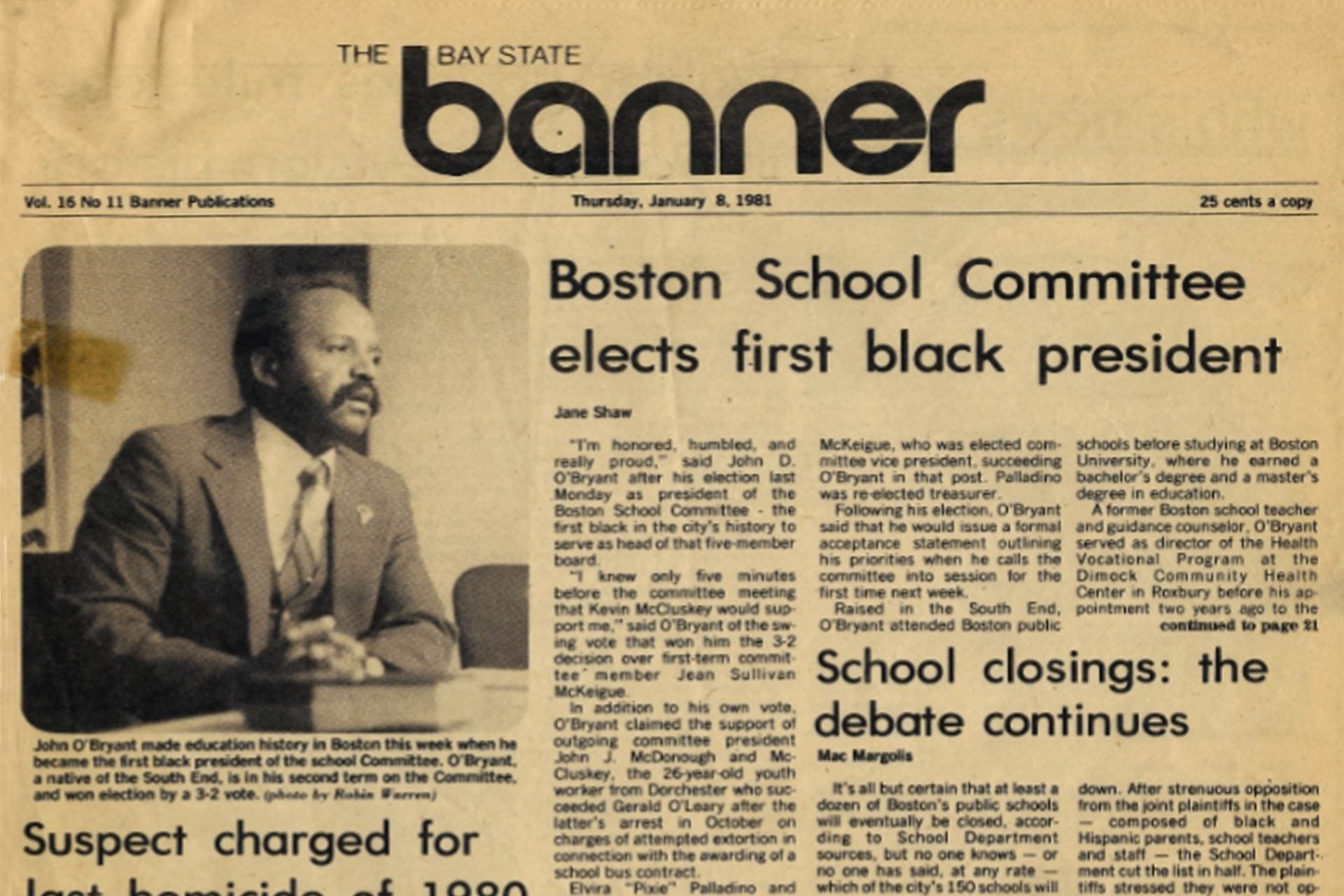

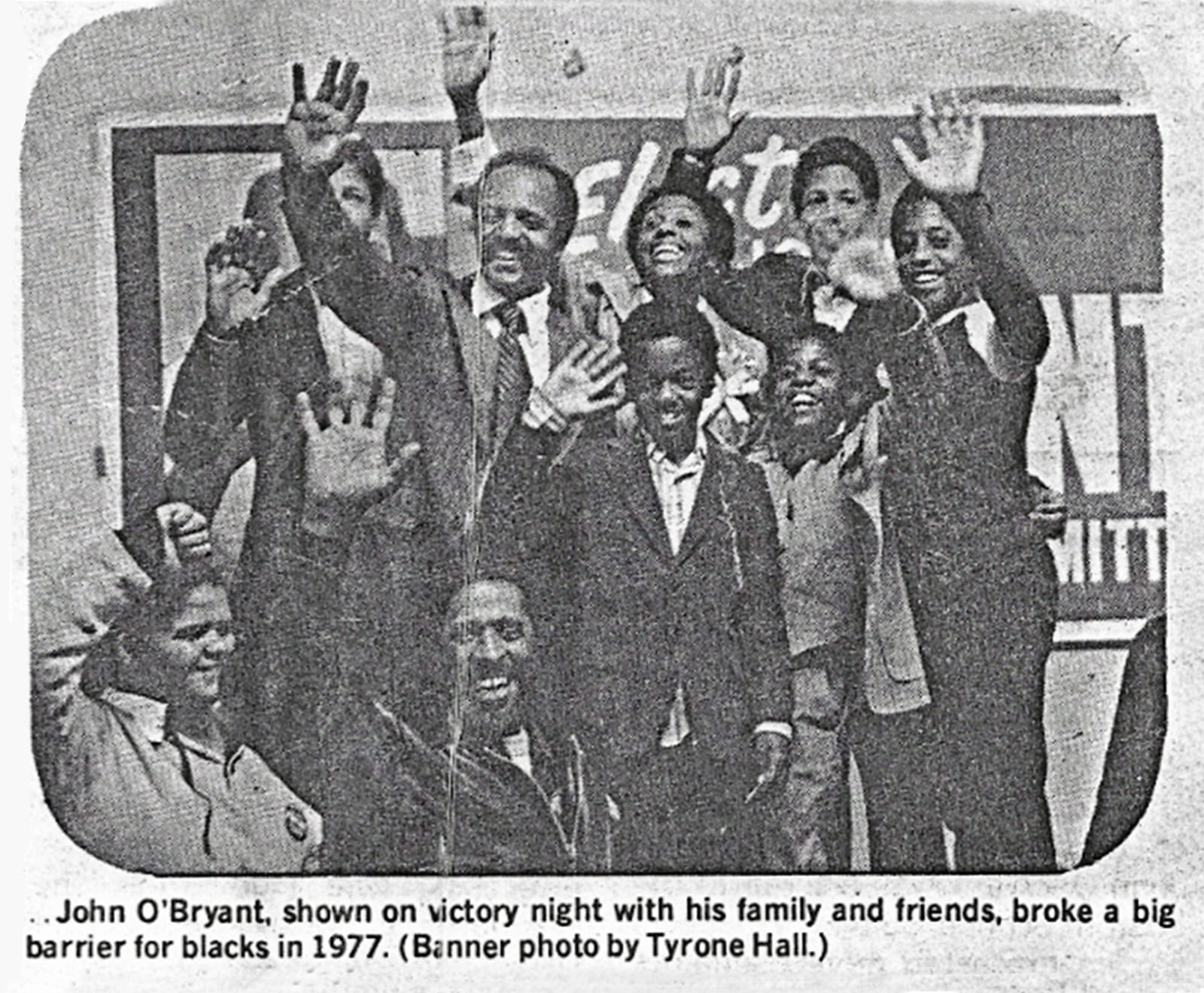

As a teenager growing up in Boston, O’Bryant and his four brothers had “a great time” working on their father’s campaigns to seek election to the Boston School Committee, which has governed the city’s public school system since the 1700s. Despite enduring violent outbursts and even death threats, former teacher and guidance counselor John D. O’Bryant was elected to the BSC in 1977—square in the middle of the Boston busing crisis—as its first African American member. He went on to become the committee’s first African American president, serving from 1980 to 1990.

“My father has a long list of firsts because of his personality, his drive,” O’Bryant said. “The whole point of his joining the BSC was to make the schools desegregated. He had a lot of people behind him, but he helped change the way all Boston kids, not just Black students, were educated.”

In 1979, the elder O’Bryant, a resolute civil rights activist, was named the first African American vice president (of student affairs) at Northeastern, where the African American Institute bears his name (as does the John D. O’Bryant School of Mathematics and Science in Roxbury, Massachusetts). Established in 1968 and renamed upon John D. O’Bryant’s death in 1992, the institute has long been directed by James’ brother, Richard, who also teaches in Northeastern’s College of Professional Studies, Department of Political Science, and School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs.

On Jan. 13, both brothers were on hand for the unveiling of “The Embrace,” a polished bronze statue memorializing Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife, Coretta Scott King, on Boston Common. Surrounding the magnificent 22-foot-tall memorial on the 1965 Freedom Plaza are the names of 69 civil rights leaders of Boston. Among them is John D. O’Bryant.

A clarion call for civil rights, the O’Bryant name is etched quite literally in the history of both Boston and Northeastern. And the eldest O’Bryant son is proud to carry on his father’s legacy by championing education and equality on campus and beyond.

For several years, he has also been working on a documentary about his father’s lifelong work: “I’m actually using Northeastern’s TV studio to interview people. Every couple of weeks, I bring someone in who worked with my father on his campaign, who knew him personally.”

While O’Bryant has already filmed Mel King, his father’s boyhood friend who was nearly elected mayor of Boston, he’s now working on securing an interview with Jean McGuire, the first African American woman to serve on the BSC. He also plans to visit the archives at Boston University, where his father captained the basketball team, an incredible feat for a Black man in the 1950s.

“Every time I read and learn more about my father,” O’Bryant said, “I feel so proud about who he was and what he did and what he stood for.”

VIDEO: James O’Bryant talks about Black History Month, his father’s legacy, and inclusivity at Northeastern.

The Call of Northeastern

After finishing his undergraduate degree, O’Bryant joined the Urban League of Eastern Massachusetts, where he developed and administered youth programs for the community. Then, upon earning his certification in education, he took a position as a middle school teacher in the Boston Public School System, but became disillusioned with the school’s management.

Changing course, O’Bryant pursed technology certifications in 2000. “I did it because my twin brother was doing technology, and I just found my niche,” he said. “By doing technology, I can teach people, and people learn as I help them with their computers.”

Newly certified in IT, he worked for several large companies, including State Street, Iron Mountain, and John Hancock, doing contract jobs, “trying to get in, fit in,” but soon realized he wanted to return to his alma mater.

“I decided to come back to Northeastern because it’s more inclusive,” O’Bryant said. “I feel included. In the corporate world, you don’t feel that you’re seen in the same way.”

“The inclusiveness on this campus is very beautiful. You feel it when you’re here. People don’t treat you like you shouldn’t be here.”

– James O’Bryant

To illustrate, he described a common occurrence that made him highly uncomfortable: “When people would all go out to lunch, and they didn’t invite me, I would ask myself, ‘How come?’ And then the next day comes, and the same thing happens. It’s something that you can’t complain about because it’s a choice that they made. You can’t say anything because it sounds like you’re whining. But that’s just stuff I had to deal with over the years. It’s called microaggression.”

O’Bryant feels that he has never experienced such mistreatment at Northeastern. “I actually love my job and what I’m doing,” he said. “I’m connected with the large community here on campus, across New England, and even abroad.”

While his goal is to retire at Northeastern, he’s nowhere near ready yet, and he still enjoys working with students, some 130 at any given time. “I train them, and then they graduate and move on,” he said. “And new students, fresh out of high school who’ve never worked a job in their lives, come in to work. You have to show them how to answer phones, how to talk to people. I enjoy that. I’m constantly helping them out and helping them grow—and helping the university grow, too.”

Taking calls daily from the campus community can be a constant grind, some days busier than others, but “I really like it,” O’Bryant said, “because I’m helping people, getting them on their way.”

Not unexpectedly, he points to his father’s example as the backbone of his commitment to education, a father who had to fight tooth and nail to continue his own studies. Although John D. O’Bryant was offered admission to Boston University in the 1950s—likely because of his Irish name—he was told to leave once it was discovered that he was African American. After securing an attorney, the elder O’Bryant went on to complete his undergraduate degree, serve in the military, and then earn a master’s degree, which led to a long, distinguished career as an educator.

“His love for education and the way he talked to people influenced me,” O’Bryant said. “He always got people thinking about building blocks in their life because you have to be educated to make yourself better. I learned that from him.”

The Significance of Black History Month

“When I think about Black History Month,” he said, “I think about how most people get the watered-down version of Black history. It was so much more than just the great leaders who are mentioned every February. There are so many more people in our history who have contributed to the building of this country: great leaders, inventors, pro athletes, artists, and poets who spoke out against injustices in our society. We must show the greatness.”

In keeping with his familial heritage and life experiences as an African American born into the strife of the 1960s, O’Bryant has ideas about how our country might better celebrate the contributions of Black Americans.

Because there were concerted efforts over the decades to subvert Black history, to deliberately keep it hidden from history books and classes to eschew accountability, “most people don’t know our history, and they don’t know that they don’t know,” O’Bryant said. “If nobody knows our history, there’s no respect given it. And that’s sad.

“Something needs to be done to change the hearts and minds of young people so that they don’t become doctors, lawyers, police officers, who don’t like people of color. The only way to change that is through education. They need to know in order to do the right thing, to know better so they can do better.”

O’Bryant believes that the wide diversity of African American lives must be revealed so that “people will have more respect subconsciously. They see a certain image of just a TV star or a great pro athlete and don’t know we are so much more than that.”

In Northeastern IT Services, for instance, he suggested that African Americans and their achievements could be highlighted in biweekly all-hands meetings during Black History Month. And few would be more capable than O’Bryant of leading such a discussion.

“I’m a Black history afficionado,” he said. “I love studying it because it’s so deep and so rich. I love telling people about what I have learned and about the people I have met over the years in Boston. I basically lived part of Black history in Boston with my father and the great work my family has done.”

Learn More

John D. O’Bryant

- Northeastern’s John D. O’Bryant African American Institute

- Beneath “The Embrace,” the 1965 Freedom Plaza honors 69 civil rights and social justice leaders active in Greater Boston from 1950 to 1975.

“The Embrace” Digital Experience

Northeastern Global News

- John D. O’Bryant, a civil rights leader of Martin Luther King Jr.’s era, is honored at new Boston Common statue (Jan. 13, 2023)

- ‘When I look at it, I see love.’ MLK Memorial ‘The Embrace’ on Boston Common elicits warmth, artistic criticism (Feb. 17, 2023)

The Boston Globe